It is very important to survey and research the ecology of orangutans in order to prevent their extinction and to protect their habitat. For this reason, we are continuously conducting research on orangutans in the Danum Valley Conservation Area in Sabah, Malaysia.

About the Research Site, Danum Valley – Mast-fruiting Forest

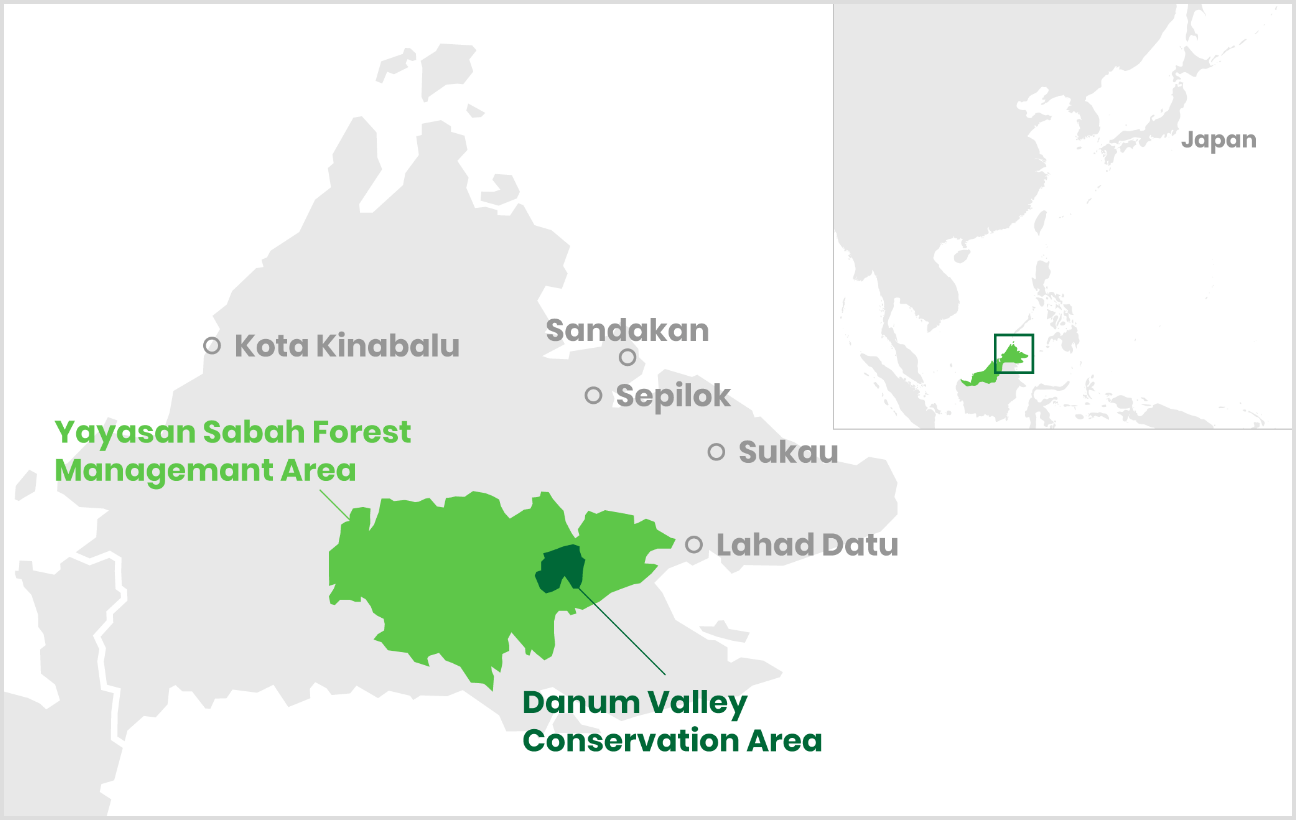

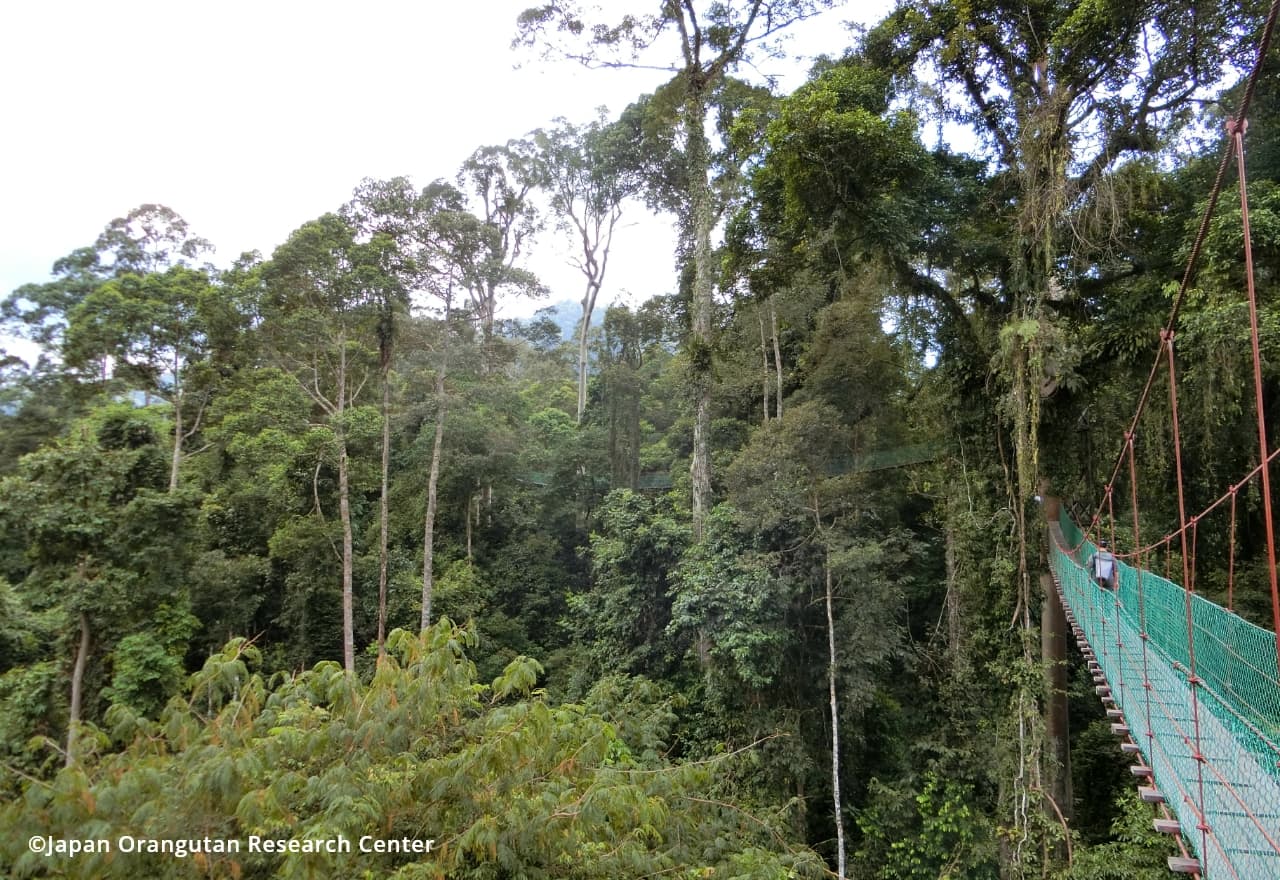

The Danum Valley Conservation Area is located about two and a half hours by car from the town of Lahad Datu in Sabah, Malaysia. It forms part of the state’s remaining primary forests, which cover only 4.6% of Sabah, and is designated as a Class I Protection Forest. Danum Valley preserves some of the oldest lowland tropical rainforests in Borneo, making it one of the most strictly protected and biodiversity-rich areas in the region.

Danum Valley is home to a rich diversity of wildlife, with 77 species of mammals, 243 species of birds, 42 species of reptiles, and 42 species of amphibians recorded (Marsh & Greer, 1992). Among them, the orangutan is particularly well known.

The unique characteristic of this forest is that it is a lowland mixed dipterocarp forest, so it has a phenomenon called "mast fruiting," in which many tree species bear fruit at the same time once every two to ten years. This phenomenon occurs only when the primary forest is dominated by native dipterocarp species. Hence, it is becoming extremely rare to find an environment where this phenomenon can be studied. During the few months of mast fruiting, the orangutans forage intensively for fruit only, consuming two to four times more calories than non-mast fruiting period and accumulating fat (Knott, 1998). Orangutans tolerate non-fruiting seasons by burning the stored fat until the next fruiting season. Our research in the Danum Valley is focused on how orangutans change their feedings, behaviors, and physiology to this phenomenon.

Importance of the research

Our research focuses on Bornean Orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus morio). Approximately 500 orangutans are living in the Danum Valley Conservation Area. This area is expected to have the same number of orangutan individuals even after 100 years, if the habitat is maintained properly. Currently, most orangutan habitats are the secondary forests, and the number of research sites for orangutans living in primary forest is very small, so these sites have become valuable as places where the "natural" ecology of orangutans can be observed. The long-term research in Danum Valley also plays an important role as a conservation project, as it can be compared with the research results obtained from orangutans living in degraded habitats.

Research in Danum Valley

Introduction to the research site

We are conducting our research mainly around the Borneo Rainforest Lodge, a tourist accommodation facility, located about 36 km away from the entrance of the conservation area. We have a small research station in the village where the employees of this lodge live, and we rely on this facility for electricity, water, and other infrastructures to conduct our research there.

Borneo Rainforest Lodge

The accommodation fee includes pick-up & drop-off services from and to the Lahad Datu Airport, and four eco-tour guides and three meals per day.

However, our research team does not use these tourist accommodation services.We are based in a research station in the village adjacent to BRL, and our studies are supported by BRL in terms of basic infrastructure such as electricity and water, as well as transport into the conservation area.

The Kuala Sungai Research Station (KSDRS), which serves as our main research base for field research, was established in 2010 through an MOU agreement between the Wildlife Research Center of Kyoto University and Sabah Foundation, the owner of the Danum Valley Conservation Area. Since 2023, it has been operated by the Sabah Foundation and the Japan Orangutan Research Center. Two to three local assistants stay in the station and live together with researchers. We only go to the nearby city only once a month to buy food, and live together and dine at the same table.

Difficulties in orangutan research

Orangutans, unlike other great apes such as chimpanzees and gorillas, have not yet been well studied.This is because they live alone rather than in groups, high in the trees of vast and dense rainforests.

As a result, finding orangutans in the forest is extremely difficult.

Finding orangutans in the forest can be very difficult. Orangutans travel alone and rarely make sounds (such as voices and rustling trees), so it is difficult to find them. Also, the reddish-brown hair color of the orangutans is similar to that of dead leaves caught on branches, making them very difficult to find. So, how can we find them? When searching for orangutans, we researchers walk slowly through the forest, looking for the smell of their feces or urine on the ground. Once we find a place with a fresh smell, we carefully look over the tree tops to find the orangutan.

Experienced research assistants can find orangutans within a half a day to a day. However, if the orangutanns' favorite fruit cannot be found in the forest, they may not be found even after a week of searching. Thus, support from local assistants is necessary to study orangutans. Because the chances of encountering the orangutans are limited and the efficiency of data collection is very poor, many primate researchers avoid studying orangutans.

Orangutans under Study

The center identifies individual wild orangutans and conducts long-term monitoring of their behavior and ecology.

Information on the individuals under study in 2024-2025 is available via the “Introduction to the Orangutans” section below.Profiles of each individual are provided.

Daily life of wild orangutans and our research activities

Here is the daily life of an orangutan and our daily research activiies.

Morning

Orangutans make a new nest in a tree for sleeping every night. We wait for the orangutans to wake up under their nests early in the morning around 5:30 a.m., a few dozen minutes before they wake up from their nests. It varies depending on the individual and the season, but the orangutans slowly come out from their nests after 6:00 am. The orangutans forage and move on to the next place where they can find foods. During this time, we will be tracking and recording the orangutan's behavior and foods at a rate of "once per minute".

Noon

Around noon, when the temperature is high, the orangutans stop moving and rest on thick, well-ventilated branches. Then, in the afternoon when the wind starts blowing, orangutans start moving again, and they repeatedly move, feed, and rest.

Evening

In the evening, when the sun is setting around 5 to 6 p.m., orangutans build a new nest and go to sleep. The nest is shaped like a large birds’ nest, and is built by repeatedly weaving thin branches inside. It takes about three to five minutes to build a nest. As orangutans fall asleep, we strain our eyes in the dark to see how the orangutans would have slept in their nests. This is the end of our research of the day, and we return back to our research station.

Examples of research themes in Danum Valley

-

Understanding changes in orangutan population (Dr. Tomoko Kanamori)

To understand the changes in the population of orangutans in Danum Valley, Dr. Kanamori has been conducting monthly surveys to determine the density of the orangutans for over 20 years. Dr. Kanamori also conducts monthly surveys on fruit availability, to determine how many trees are fruiting in the forest. This result of fruit availability is compared to the population density of orangutans. Such comparison, for example, reveals that the population density temporarily increases as orangutans gather to eat fruits during the fruiting season.

-

Understanding the forest through food (Dr. Tomoko Kanamori)

Ninety-nine percent of the food eaten by the orangutans in Danum Valley is plants. The variety of edible species is very rich, with over 365 species in 174 genera in 73 families of fruits, leaves, barks, and flowers. By investigating how much varieties of flora is needed for orangutans living in the primary forest, Dr. Kanamori hopes to understand the ecology of primary forest in the Borneo Island.

-

Understanding society through parent-child relationships (Dr. Tomoyuki Tajima)

Because orangutans are solitary, we can know very little about their kinship, such as paternity, from behavioral observation. Dr. Tajima is collecting feces from orangutans and analyzing their DNA to investigate their kinship. DNA analysis reveals kinship among orangutan individuals, which clarifies the understudied society of solitary wild orangutans.

-

Reproduction (Dr. Noko Kuze)

Dr. Kuze studies the reproduction of orangutans by collecting their urine and measuring their hormone levels. Females only come to estrus every 6–9 years, it takes a long time to collect data for this study.

-

Development of immature individuals (Dr. Renata Mendonça)

Dr. Mendonça studies the behavioral development of immature orangutans aged between 1 and 7 years old. Dr. Mendonça clarified the characteristics of the transition process from infancy, when the child is dependent on the mother, to the juvenile period, when the immature individulas learns to forage, move, and play around the mother.

-

Biomolecular investigation (Dr. Takumi Tsutaya)

By analyzing the proteins and tracers of orangutans’ feces and bones, Dr. Tsutaya investigates their diet, breastfeeding and weaning patterns, and health status. By analyzing various molecules contained in the samples, the life way of orangutans can be revealed , which could not be determined from behavioral observations and DNA analysis.

Why do orangutans need long-term research?

Orangutans are slow-growing animals with a long life expectancies (estimated at 50 – 60 years). Our 20-year research activity is only equivalent to one third of an orangutan's life. To accurately understand the ecology of orangutans and to ensure that their population does not decline, we need to continue research as long as possible.